For weeks now we in the running world have watched the excitement for the 2016 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials grow across social media. But as a who’s who of American long-distance running finally convenes in Los Angles for tomorrow’s big race, we’re happy to see support for the two Native runners toeing the line erupting from every corner of the “interREZ” . Craig Curley (Diné) and Linnabah Snyder (Diné) have been working hard for YEARS with a vision of tomorrow in the back of their minds. They deserve all the well-wishes and support they can get. Especially for Craig, a former Wings National Team member, we share Indian Country’s high hopes.

Craig Curley crosses the finish line first in 2:19.01 at the Columbus Marathon on October, 21 2012 (Photo by Eamon Queeney)

But unlike the thousands of friends and family members currently voicing support for “their” competitor in tomorrow’s field of 455 (men & women), those pulling for Craig and Linnabah are rooting for more than just a runner. They’re rooting for a legacy of success and the idea that Native athletes deserve spots in competitions with the best in the world. Encouraged by the memory of Olympic performances by Billy Mills and Lewis Tewanima, Native people who line tomorrow’s course or tune in to a live-stream to catch a glimpse of Craig or Linnabah will be cheering for Native America, in general. Because if any “tradition” pervasive across Indian Country has the ability to show the outside world Native people are alive and well, it’s running.

With this in mind, we not only wanted to take the time to remind Craig and Linnabah how proud of them we are, but also educate those paying special attention to running right now about the storied history of Native marathon runners in Los Angeles. As they stride through the streets of the City of Angels tomorrow morning, runners will follow in the footsteps of Native champions before them:

Though they were contemporaries of Lewis Tewanima, you hear the names of Hopi runners Philip Zeyouma and Guy Maktima much less-often. But as representative of Sherman Indian School, the pair shocked the field of the Los Angeles Times Modified Marathon (12 miles) in 1912. By winning, Zeyouma selected himself as the “western candidate” to represent the U.S. in the Olympic Marathon in Stockholm later that year. But as Hopi scholar and professor Matt Sakiestewa-Gilbert explains in his 2010 American Quarterly article “Hopi Footraces and American Marathons, 1912-1930”, Zeyouma’s victory may have been more-significant because it, “challenged white American perceptions of modernity and placed him in a context that had national and international dimensions” (pg. 78).

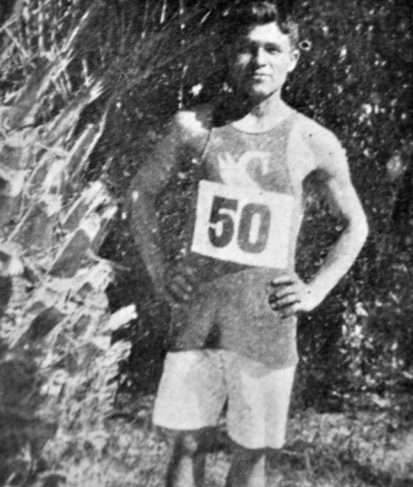

Philip Zeyouma at the 1912 Los Angeles Times

Modified Marathon. Zeyouma is wearing a

shirt that depicts the flying snake of the Hopi.

Photograph courtesy of the Sherman Indian

Museum, Riverside, California. Accessed on “BEYOND THE MESAS” 2.12.2016

In the end, Tewanima was the only Hopi to compete in the 1912 Olympic Marathon. Zeyouma went back to The Rez for the summer at his father’s request (Sakiestewa-Gilbert, pg. 87). Interestingly enough, we continue to see this tension between “new ways” of competitive running and “old ways” of work “back home”. Many of you probably know by now that Craig Curley was forbidden to go out for the cross country team when he first developed an interest for the sport. Fortunately the conflict didn’t last so long that it discouraged our talented brother from competing altogether…

Once more in June of 1929, a Hopi representative from Sherman Indian School managed to steal the spotlight in the Los Angeles Times pre-Olympic marathon. Though two other Hopi runners, Franklin Suhu and Howard Tsemptewa, helped out in the beginning of the race, nineteen-year-old Harry Chaca of Polacca eventually wore down the 1927 Boston Marathon winner, Clarence “Melrose Marvel” De Mar, to break the tape (Sakiestewa-Gilbert, pg. 90). A mob of excited spectators waited to congratulate a Native runner who was seen as little more than a member of an inferior race by the same crowd before the gun went off. Later that year, the famed Japanese marathoner Yoshikiyo Sudsuki travelled to Vallejo, CA specifically to race Chaca. Thus, similar to Tewanima and Zeyouma before him, Chaca “became a representative of the United States, and the marathon became a contest between American nationalism and Japanese imperialism” (Sakiestewa-Gilbert, pg. 92).

So rather than be bombarded by click-bait for discounted running shoes while reading about Craig of Linnabah on another site, we once again encourage any readers that made it this far to read Sakiestewa-Gilbert’s “Hopi Footraces and American Marathons, 1912-1930” in full (click title). You may also want to check out his blog, Beyond The Mesas, for even more well-researched information about Native running luminaries. Not only will you gain further insight into what drives that burning pride we Natives feel for talented runners from our communities, but you might also understand more about how important it is that Native competitors are still representing Indian Country on such an elite level as the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials. As more and more professional runners turn to specially-formulated recovery drinks and access to underwater treadmills to keep up with their peers, these blue-collar athletes from “back home” help remind us why we’re proud to be Native. Perhaps it will also get at least a few of you thinking about how we can better support Native distance runners in Olympic qualifying years to come. Somebody’s gotta step up to protect Billy Mill’s legacy in Tokyo come 2020…